A Century Of UK/NI Rainfall (part 6)

A butcher's at drought and deluge over the last 100 years. Are things getting worse, and what does ‘worse’ even mean?

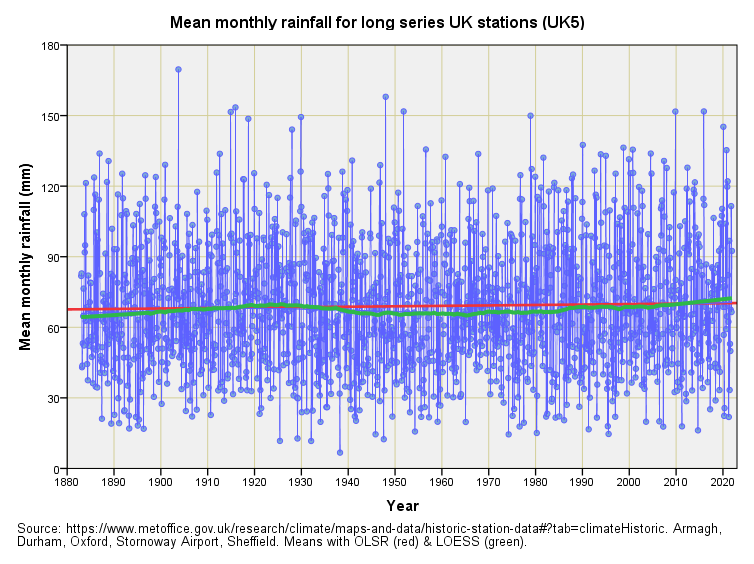

In part 5 of this series I promised to stop farting about and get to producing a slide of monthly mean rainfall for the UK since the turn of the last century for what I’m calling the ‘big five’ (a.k.a. UK5 or Les Cinq), these being stations at Armagh, Oxford, Stornoway Airport, Durham and Sheffield who have put their buckets out continuously since 1883. Not many weather stations on the surface of the Earth have collected rainfall data as diligently as this for this length of time and so we may call them stations of global significance. You can grab the data for yourself from here.

Here’s Two I Baked Earlier

In the top slide of this pair we observe monthly rainfall averaged across the five stations in the sample. I’ve plonked down one of those ubiquitous OLSR trendlines (red) and a LOESS regression (green). It’s difficult to determine much by way of underlying trend because the series is pretty darn stationary (a fancy word meaning ‘flat’). What we can do is eyeball the frequency of spikes both up (deluge) and down (drought) to find things have remained pretty much the same over the last 139 years, though I shall be tackling this issue in a more formal manner in a future newsletter.

In the bottom slide of this pair I’ve averaged across the five stations in the sample as well as across the year to give what I am calling ‘annualised means’. With the monthly clutter gone we can now see the wood and the trees. Straight line thinkers will adore the OLSR red line, which is yielding a positive slope of +0.018mm monthly rainfall per year, this being statistically insignificant (p=0.210). To all intents and purposes nothing has changed over time, though the LOESS regression (green line) suggests a tendency for intermittent wetter and drier periods, with the series showing an upward trend toward wetness from 1950 onward. Stats geeks will no doubt ask whether the entire series is nothing but a random walk and they’d be right (p=0.821, nonparametric one sample runs test).

So What About That 1950 Trend?

If we start our regression analysis at 1950 we get this result:

This tells us that there is indeed a statistically significant positive trend (p=0.027), which is proceeding at a rate of +0.09mm per year. This isn’t a lot but it does indicate that things have been getting slightly wetter at the five long series stations in the study. There are several possible reasons for this one of which is hypothesised man-made climate change, though they’d have to concede that the UK is heading for deluge rather than drought if this is indeed the case!

When I can find time I’ll see how this annual pattern relates to solar cycles, cosmic ray flux and oceanic oscillations, particularly the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC).

Drought Or Deluge?

All exciting stuff but for the time being let us hark back to the crowded monthly series for mean rainfall and define periods of deluge and drought. A quick run over the data series with towels reveals a range spanning a minimum of 6.7mm and maximum of 169.6mm, with 5 and 95 percentiles turning out at 29.4mm and 116.8mm respectively. Let us use these values as the cut-off points for our drought and deluge proxy indicators.

N.B. Please bear in mind that these definitions are based on what is landing on our heads; water management amongst population growth is entirely a different matter!

We can now count extreme periods we have defined for each of the 12 decades from 1900 onward, thus:

There’s a great deal we could cogitate on and suggest at this point but one thing is perfectly clear: periods of (precipitation-driven) drought in the UK are not steadily increasing over time as alarmists claim. The ‘80s were certainly a drought-ridden time but no more so than the ‘50s or ‘40s. Indeed so, for the ‘00s were less drought riddled than the ‘20s and the ‘00s at the turn of the last century. What we don’t see here is evidence of man-made climate change; what we do see is abundant evidence of climate change pure and simple. If hosepipe bans and other threats are going to become commonplace then I suggest we look to water management in expanding urban areas rather than zero carbon solutions: one of these approaches will produce results for the benefit of the many, the other will produce results for the benefit of the few. But let us move along the bus…

In the analysis of annualised monthly means three slides back we noted a positive trend in rainfall from 1950 onward. Here is that same trend but in terms of increasing counts of seriously wet months. It’s getting wetter folks, and that means more cloud cover!

This is where it gets funky because clouds have a profound cooling effect yet are ignored in Earth systems models (currently at the CMIP6 stage of development). This is largely because we don’t understand them. Certain experts think they do but these folk haven’t come up with decent models of how clouds behave, so clouds get short shrift in the modelling community, who tend to regurgitate vacuous statements such as “clouds are a symptom of climate change and not a cause”. There’s at least one serious scientist who thinks there may be more to clouds than this and I recommend this documentary as a starting point.

My own home-baked research since 2017 points to cosmic aspects to climate change that have gone unaddressed within the modelling community, which is one reason why emphasis is placed on fossil fuels leading to radiative forcing by increased atmospheric carbon dioxide. Not only do they find the fossil fuel scapegoat easier to house-train (settled science etc) but they are also awarded grants strictly on this basis. There are equally valid alternative explanations for what we may observe for Earth’s changing energy budget, and I shall be exploring empirical evidence for these in future newsletters.

Next up…

With a methodology in place for yielding half-decent estimates of monthly UK rainfall since 1883 I may as well run the towels over temperature data to see what we may see in that regard. We can then bring temperature and rainfall together and throw in hours of sunshine (there go those clouds again) plus a few other surprises. With a pantry brimming with goodies like this we can also take a quick look at the urban heat island effect. I reckon we need another packet of biscuits!

Kettle On!

I'll second that, JD.

I hadn’t seen Svensmark’s movie but I did read his book about six years back. Now if we are looking for big time climate change drivers, you might find Paul A LaViolette’s “Evidence for a Global Warming at the Termination I Boundary and Its Possible Cosmic Dust Cause” (0503158.pdf) is even more mind blowing. It’s hard to believe such iconoclastic empirical evidence researchers get so little attention. On the subject of Global Energy Budget, I assume you have found the GEBA database https://geba.ethz.ch/ ETH Zurich. Martin Wild published a free paper on the veracity and extent of the data. I’m still struggling to find more about the UK stations.

Thank you for all your hard work!! I'm starting to understand more, slowly but surely. Are there definitive conclusions coming down the road?